The quick loop

A deep breath. Another one. Let the cooler air of the shaded understory inflate my lungs to their point of maximum elasticity. Let it out slowly, warmed and chemically transmuted by its moments within the miraculous feat of evolutionary engineering I call “my” body. I begin, habitually, to translate the sense information received from the inhalation into words, to piece apart the smells (dead leaves, sweet earth, the marshy funk of riparian low tide rising on the breeze) from the experience of smell itself. Then I stop where I am, self-conscious, to put my hand to my heart and try again: One deep breath. Another one.

I’m here to make my loop—the quick one. I know many foragers who range deep and far and often into new terrain, seeking out a forest’s secrets with the spirit of an explorer. I’ve come to accept that I’m not one of them. Perhaps it’s an overly elaborate excuse for having no internal sense of direction whatsoever, but I tend to take a more Stoic view on exploration and travel. If the highest goal of adventuring into the unknown isn’t just the fleeting high of novelty, but rather to send that questing tap root we call curiosity back into the world…then where is that spirit really more needed than at home? Who needs us to witness them with fresh eyes and a receptive mind more than our own family, than the land, than the more-than-human community we live our day-to-day existence within?

For these and other reasons—namely, long habit that has morphed into devotion—the vast majority of my time in the woods is spent at two or three parks, and out of those mostly the one a quick 5 minute drive from my house. The days, stretching recently to weeks, when I claim to not have time for this moment—not of solitude, really, but of reintegration into a whole—tend to be the times I most require it. I know this, and yet. And yet. Anyway, here I am.

I start my loop. Which, for the record, I understand is not “mine” in any legal or spiritual sense of exclusivity, but has nevertheless has become so much a part of my mental landscape over the years that its changes, both cyclic and progressive, register as intimately as those of my own body. Observing the inexorable spread of stiltgrass year over year akin to watching my eyebrows grow out white and utterly ungovernable one at a time. I know I can’t really control, much less reverse the situation, and yet I can’t help feeling responsible.

As a mushroom person, and beyond that a moss person, a lichen person, a slithery little critter person, my eyes and whole attention tends to be drawn down to the duff, locked tight against the boundary layer that hugs each log and glacial boulder I pass. It takes physical effort to remind myself that a canopy—as grand as a cathedral, as green as daydreams—exists just overhead. All I have to do is tip my chin up and, like a radio antenna wiggled to perfection, the birdsong suddenly comes through, sharp and clear and lovely as dawn. It’s an experience of heavenliness and I completely understand the appeal of birdwatching…but always my eyes are drawn down. Who’s there, nosing a ruddy dome up from beneath the leaves? Who’s there, gathered upon a single leaf, holding aloft a dozen of the teensiest white umbrellas?

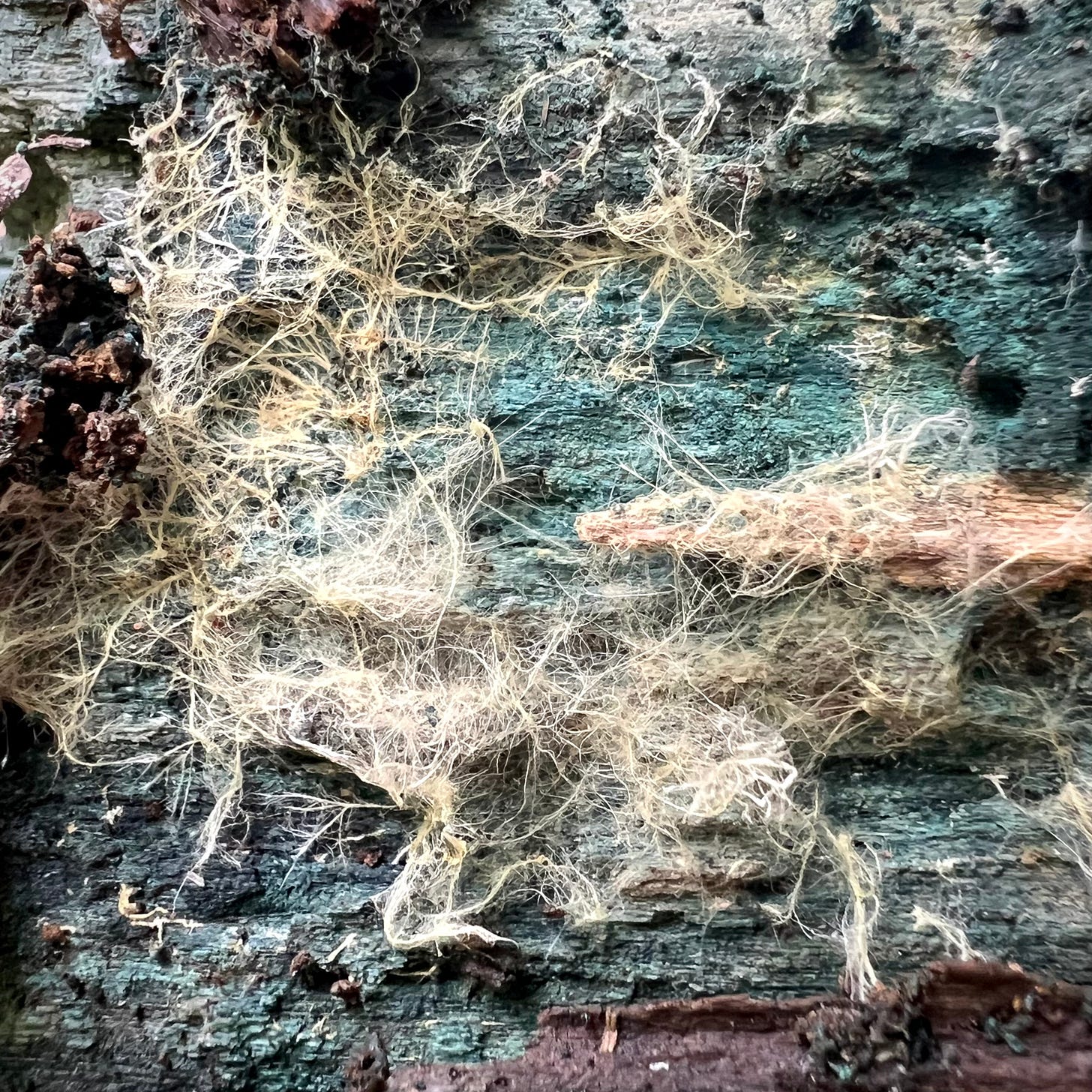

Season by season, year by year, my long-term memory holds onto the location of mushrooms with a tenacity I truly wish it would apply to some other, slightly more practical life data. Walking along the path as it rises higher and the creek beside it drops away, I absently check areas I know to be the home of some of my favored mycorrhizae: milkcaps, chanterelles, boletes of many stripes. The conditions have been favorable, I wouldn’t be surprised to find these old friends waiting, but no one’s home today. I glance downhill at a log which one year sported Stereum ostrea so thickly it looked like nothing so much as glorious plumage—maybe dinosaurs looked like this. The next year the mushrooms grew thinner, but still feathered out. The year after it a thick moss grew in and turned the much-softened trunk into a bed of green. How long ago was that? The small army of decomposers that have been working on the once-tree for years are nearing the end of the project. A dark russet hillock is all that remains.

Come take a mushroom walk with me this Sunday ~~ Spots for my next foray at Opus 40 are still available here.

Walking this loop is a small bit of exercise, but more-so for me now it’s an exercise in accepting the flow of time and the inevitability of change. The mycorrhizal fungi, bound as they are to the root-tips of particular trees, mark a cyclic return with their fruiting—not a stable, static loop, not a holiday on the Gregorian calendar—but a return to a particular constellation of conditions we will (at least if we shape up in time to avert a full climate collapse) continue to revolve back to at irregular, ecstatic intervals

Decomposers are not like that. For saprophytic fungi, their home is their food and their food is their home. It may take one year to consume or ten, but there is no mirage of forever for the decomposer. Seeing the ferns grow around, into, over the spot where a splintered, emerald-encrusted stump in all its “fairy house” glory once stood is gut-clenching reminder that my child has doubled in height since I first recall her squatting there, a diaper poking from the waistband of her ankle-length shorts. I can remember her open palm, as soft as the moss she pet. She will never be that doe-eyed toddler again, any more than this patch of earth which was once a stump which was once a tree will shade us on our walks together.

One deep breath. Then another. It is beautiful, challenging work: to love without grasping onto what was. To allow the landscape of our lives its changes, from the tiny to the tidal. And then, with a little luck, perhaps to gift ourselves the same.

Apologies for the longer-than-anticipated break in The Oyster Log. I had thought a month would be sufficient for book promotion, but a subsequent spiral of injury and care needs proved me wrong. With some time to think along the way, I’ve come to realize that writing this newsletter feels like one of the more meaningful things I do in the world, and also that I probably cannot keep up a weekly pace at all times while attending to the rest of my life the way I want and need to. The week is an invented unit of time, whereas growing children and aging elders and caring bodies cresting into middle age, all dependent on each other, create rhythms both unique and unpredictable. Moving forward, if I can figure out how to write shorter posts on wilder weeks, I’ll do so. And if I cannot, I’ll try to make what I write the next week worth the reading. As always, I so deeply appreciate the time you spend here, and all the myriad connections that have come from sending these little hyphal threads out into the ecosystem.

“To love without grasping onto what was…”

Chris, this post read like a poem to me, or rather, felt like a poem deep in the heart of the body I call “my” body. Thank you for this treasure. Happy you’re back, hoping you’re healing. Love you.

thank you for the morning tear-jerker to be with the ever-shifting. the vignette about the fairy house stump decomposed alongside toddlerhood got me 🥲 appreciate your attention to the land/body and your words arising from that cyclical relationship 🤍