My heart and brain are still overflowing from this past weekend. I was very fortunate to be able to carve two days away from my already overflowing daily responsibilities to attend the Northeast Mycological Federation (NEMF) annual foray, held this year at the Soyuzivka Ukrainian Heritage Center in Kerhonkson, NY. I would have been there anyway to learn learn learn, but was honored when John Michelotti invited me to also present.

I’m still metabolizing everything I took away from the weekend—new knowledge, new friendships, deeper understandings of core concepts and the more ineffable benefits of immersing yourself in the company of people who share your passion. Those new inputs will undoubtedly inform my topics moving forward, but for today I wanted to share from my presentation on—of course!—golden oysters. At the end I will also invite y’all to participate in a couple projects moving forward, should you be interested~

Golden oysters, Pleurotus citrinopileatus, are the first documented case of a mushroom which was brought to North America to farm escaping cultivation, naturalizing, and spreading rapidly within multiple bioregions. This is a common and established pattern in the realm of plants, but until now there has not been an example of it happening with macrofungi. Based on accepted definitions, it would be fair to say that golden oysters are staging an invasion in North America, though for many good reasons we may decide to avoid the language of “invasive species.”

Golden oysters are fairly easy to identify, sharing many distinctive ID characteristics with other oyster mushrooms, including those available in many grocery stores. They have:

a clustered growth habit

lemony yellow caps, 3cm-8cm wide, with a central depression

whitish, deeply decurrent, distant gills

in-rolled margin (edge of the cap) spreading with age

pale pink/pale lilac spore print

As far as an ecological niche, oysters are a primary decomposer of hardwoods, preferring elm, oak and beech. They fruit early and prolifically over a long season—here in the Hudson Valley they may emerge as early as April and fruit through to the hard frost in October/November. The joke among those who have developed a relationship with golden oysters is that it’s less foraging than visiting the grocery store, as you can more-or-less mark you calendar to return to a golden oyster log a little over a month from its last fruiting, and chances are it will be fruiting again.

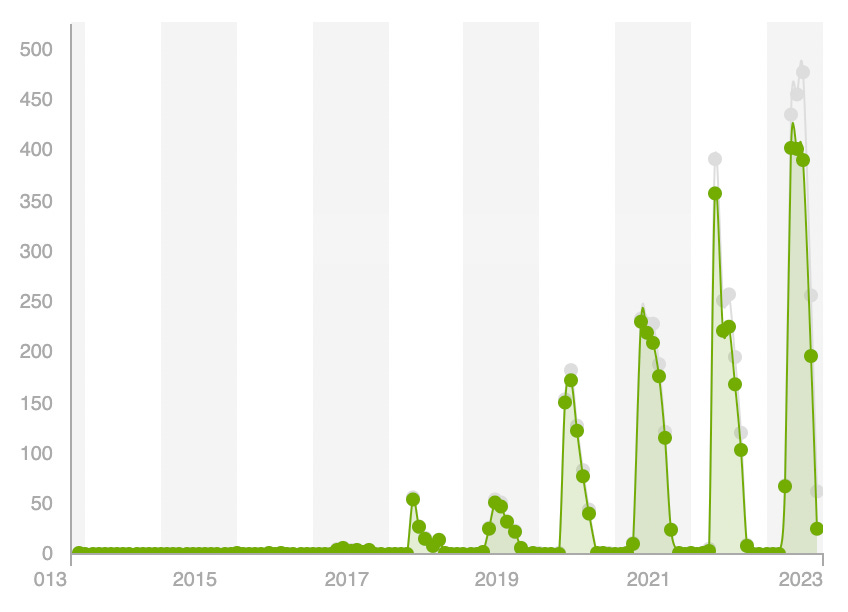

Like many in the Pleurotus genus, P. citrinopileatus is highly nutritious, delicious, potentially medicinal, and easy on the eyes. They’re also extremely easy to cultivate. A highly adaptable white rot fungus, they have been successfully trained to digest food sources as extreme as cigarette butts and other plastics, so it’s a cinch to grow them on more traditional substrates like logs, straw or cardboard. For all these reasons, they were imported to this continent in the early 2000s as mushroom cultivation was rising in popularity. Though we lack a firm timeline, anecdotal reports mark their naturalization process as starting around 2012.

Many tales have circulated explaining how the golden oyster escaped cultivation, from a hurricane to a tornados to a mushroom farm fire. However some of the only published research to date on the spread of golden oysters in North America debunks all of these ideas. For her M.A. thesis at Dr. Todd Osmundson’s lab at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, Andi Bruce sequenced 29 wild P. citrinopileatus samples from six different states, as well as six commercially cultivated strains. Her data strongly suggests that just two of the cultivars were the progenitors of all 29 wild specimens.

Based on the geographic distribution of the samples however, her conclusion was that no one catastrophic event could be held responsible for the introduction of golden oysters to the wild. Rather the most common-sense, but less appealing (due to the implication for future escapes) explanation prevailed: that outdoor cultivation and/or outdoor disposal of home growing kits introduced those two strains to multiple locations in approximately the same time frame, as they became commercially available to growers and kit-makers in the bioregions. The answer, to call back to our previous two weeks discussions, comes down to the remarkable power of ~~spores~~.

While the first observations of wild golden oysters in North America came from the midwest, and that region remains an epicenter for their spread, within a few years we have accounts of it in the northeast as well. I can personally remember finding it as early as 2016, still in the early stages of my fungi obsession. The first iNaturalist observation in the northeast was logged in 2018 in Rhinebeck, NY, due east across the Hudson River from where I live.

Interestingly—and perhaps importantly—the climate range where golden oysters have found a foothold in North America is quite dissimilar to the subtropical hardwood forests of eastern Russia, northern China, and Japan which comprise its native habitat. It has been able to spread rapidly in higher latitudes than its native range, and one explanation is our long dormancy period here in the north. In more southern states, where the climate is more conducive to fungal growth year-round, there are white rot fungi producing mushrooms in every season. However as one of the very first saprobic (decomposer) fungi to fruit at the first blush of spring here, they gain a competitive advantage over native fungi filling the same niche.

So what do we know about the rise of the golden oyster? How has it impacted the native flora, fauna and funga, and what will the knock-on effects be in years to come? In her thesis, Andi Bruce writes, “Possible alterations to native communities include the decline or loss of less competitive native species, shifts in resource availability, and the creation of novel hybrid species.”1 Breaking that down a bit further, the three “buckets” of major concern are:

the decline or loss of less competitive native species - Many native fungi are reliant on the hardwoods that golden oysters are currently dominating. If they cannot compete for those resources, we may see serious decline or even loss of those species. Displaced fungi may include native oysters (a current dissertation at the Pringle Lab at UW-Madison seeks to study this possibility2), dryad’s saddle, turkey tail, and other white rot fungi. It’s important to remember that many species of fungi don’t make large, colorful, or charismatic fruiting bodies—which shouldn’t make them any less worthy of conservation

shifts in resource availability - Fungi aren’t the only organisms to utilize dead wood. Many insects use dead trees as habitats; birds and small mammals eat the insects and also use the trees for habitats; some insects, mosses, lichen and bacteria are decomposers of dead trees…the list of organisms who rely on gradually decomposing wood is long, and includes all realms of life. Anecdotal evidence has shown that golden oysters decompose trees at record speed, perhaps as quickly as five years, which can’t help but impact the pantheon of wood-dwellers.

creation of novel hybrid species - Golden oysters have demonstrated their ability to cross with native oyster species, including Pleurotus ostreatus. Given sufficient time and spread, it’s conceivable that a more competitive hybrid of the two could displace the native oysters altogether.

For my money, the last of those concerns is the least of them, as I don’t put stock in “genetic purity” conservation models on principle. The second concern is critical on many levels, but will also likely be somewhat easier to estimate, once a real baseline for the speed of decomposition is established. The first concern is probably the prickliest…The very unfortunate fact is that when it comes to fungal conservation, the biggest issue is always a dearth of baseline data. Compared to plants, animals, and much of the life we see around us each day, fungi are poorly understood, understudied and radically under-resourced both in academic and conservation settings. Unless you happen to have say-so in funding these areas, the next best thing you can do is to contribute your mushroom observations to the Fungal Diversity Survey (aka the only North American conservation organization devoted to fungi).

Which brings me to how you can get involved! You may have noticed that the two labs referenced here as conducting research into golden oysters are both at the University of Wisconsin. If you have an oyster log (or several) you visit regularly, Todd Osmundson’s lab at UW-La Crosse is still gladly accepting samples for future sequencing projects. Scroll to the bottom of Bruce’s site to find the submission guidelines. Or if you want to go several steps further (or know someone who might), Dr. Osmundson is currently seeking a Master’s level student interested in continuing this research.

Next, if you cultivate mushrooms… please take the potential risks to the broader ecosystem into consideration when deciding which fungi to cultivate (regional vs imported strains), where and in what conditions to grow them (in controlled conditions vs outside), and how you dispose of spent substrates. There are no cut-and-dry prescriptions for being in right relationship to the land, but I do believe we have an obligation to build our awareness and to shift our actions as we metabolize new inputs.

Lastly, if you have a favorite golden oyster recipe you’d be interested in sharing, please get in touch! Over the next year I hope to collect a wide variety of home cook-level recipes that make great use of this problematic fave for a golden oyster cookbook zine. The goal of the project will be to raise awareness of both the ecological issues raised by golden oysters, but also this amazing, nutritious, abundant food source just, ya know, growing on trees. I would also love to hear from anyone with novel ideas for stewarding native saprobes, anyone who has written odes to the oyster or made a cool sketch of them, or any other hitherto unimagined contributions!

https://minds.wisconsin.edu/handle/1793/79004

https://modernfarmer.com/2023/05/is-your-favorite-new-mushroom-eradicating-native-mushroom-species/

Hi! Just found a flush here in the Western Catskills. I’ve encountered them before in the Hudson Valley but never up this way (near Roscoe, NY).