A spore print is exactly what it sounds like—a print made by mushroom spores! Ferns (and conceivably mosses and lichens) can also make spore prints, but here I’ll be focusing on those made by mushrooms, as they are a critical feature for identifying and documenting certain fungi. Spore prints can also be ~~beautiful~~ and are a wonderful way to engage with mushrooms on a tactile level without eating them. Foraging isn’t for everyone, but getting to know your local funga absolutely can be.

Last week we took a journey through some of the amazing variation in fungi spore dispersal methods—from volcanic puffballs to spore-dripping spines to your standard issue gills. This week I’d like to take you in for a closer look at the spores themselves. I hope to one day have an adequate microscope set-up to get us really up close and personal (spore size and shape can only be observed through good magnification), but for today we’ll be staying at the comfortable distance of the tabletop.

The most salient characteristic a spore print can tell us is color. Anyone who has picked up a little brown mushroom to identify for the first time has likely run into the unfortunate truth: the realm of mushroom ID can be an absolute muddle when it comes to morphological features. Leaf through a field guide or tab around on mushroomexpert.com and you’ll find, time and time again, close lookalikes aren’t necessarily closely related in the realm of fungi. (This is especially the case since genetic sequencing continues to bring about huge, messy, divisive revisions of fungal taxonomy.) Spore color isn’t the be all and end all ID characteristic, but when you’re lucky it’s a one-step shortcut that gets you in the neighborhood.

Of course, spore color isn’t always clear cut. Have you ever been to the paint department with a partner or roommate, all set to find the perfect shade of “sage” for the living room, only to find the two of you holding a couple of very different paint chips—each completely convinced that the other doesn’t understand the intrinsic nature of sage? As far as I know this is an ubiquitous issue with humans and color perception, and it certainly applies to spores. In preparing for my presentation on golden oysters at NEMF this weekend (more on that next week!) I read from three reputable sources that they drop “white,” “pale lilac” and “pale pink” spores. I took a print to look for myself, and I’d go with very pale pink. Who am I to say though? Perceptions are fungible.

To make a spore print, you need three things: a fresh, mature mushroom, a printing surface, and a relative lack of airflow. For the mushroom itself, you'll need to pick it at the prime moment when it is fully mature (and so dropping spores) but still fresh enough that it hasn’t completed its task and/or started to decompose. This is a different window for every fungus: sometimes just hours, sometimes a couple days, sometimes months in the rare case of more durable polypores. Generally speaking, you want to pick specimens whose gills (or pores or teeth or ridges etc.) are fully open but not noticeably goopy or desiccated. To prepare for the print, cleanly cut the spore-bearing surface, most likely the cap, from the stipe or other anatomy that would get in the way.

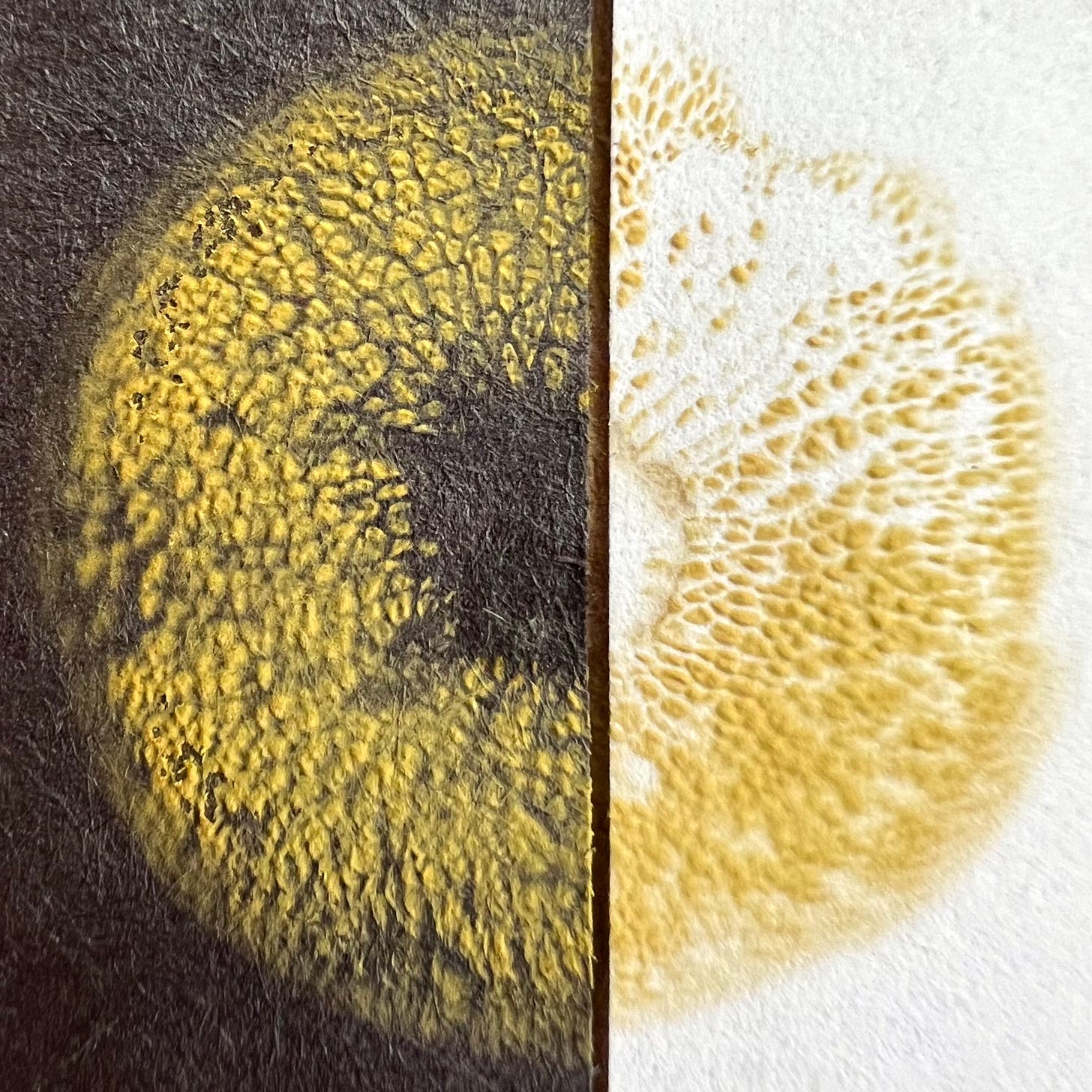

Next you’ll need an appropriate surface. If you’re cheating and already know what color the spores are likely to be, pick the most contrasting color—white for dark spores, black for light spores, dealer’s choice for the ochre-salmon range. If you’re not sure what you’re going to get, there are a few other options. If you have both light and dark paper, you can simply lay them side by side and put the mushroom spore-side down right in the center (as above). Or if you don’t care about preserving the print, there is also the simple and very accessible option of using a piece of tin foil on a plate, as any matte color will register on that shiny surface. Lastly, you can get a dedicated piece of glass to use for spore prints. Once the print has registered, you can set the glass over any contrasting surface to assess the color, then wipe clean for the next use.

In anywhere between a couple and twenty-four hours, your mushroom should release its spores onto your chosen surface. If it hasn’t within a day, it’s more than likely not going to. Better luck next time. As for the last need, a relative lack of airflow, that is only really a concern if you are hoping to preserve the print. Passing breezes will lead to wispy, trailing, ghosty prints. You can, if you care, prevent that by putting your set-up in a closet, or covering it with a bowl—just don’t forget about it! In addition to the spore color, a really crisp spore print (not pictured, lol) will also leave a legible negative of the fertile surface itself—the size, the shape, plus the size and shape and distance of the gills or pores, etc.

If you happen to find an interesting or rare mushroom, or are participating in a community science project, you may want to preserve a high quality spore print as part of your submission to a fungarium or lab.1 You can also make them for beauty! For pleasure! For the experience! If you want to turn those prints into wall art, or mail them to a friend, just spray with an artist’s fixative (as you might charcoal) or even hairspray if you have it.

It’s also worth noting that you don’t always need to take a mushroom home to print in order to assess spore color. Sharpen up your eagle eyes and check the leaves under the cap for spore deposits. For mushrooms with a clustered or overlapping grow habit (like oysters, jack o’ lanterns or chicken-of-the-woods), the caps of the lower-stationed mushrooms might bear a print. Sometimes the stipe of the mushroom itself tells the tale, as with the Cortinarious sp. above. The web-like veil material that covered the mushrooms young gills still clings to the mature mushrooms, and you can see clearly the reddish-brown spores that have gathered on it.

Lastly, if you’re interested to do more hands-on mushroom exploration, a quick plug: Fall mushroom season is upon us and an excellent season it is. If you live in or adjacent to the Hudson Valley and would like to come on a guided foray with me, I have my three final walks of the season coming up at the end of September and early October! Check out the calendar here. One of those walks happens to be at the second annual, homegrown, super exciting For the Love Fungi Festival in New Paltz, NY Sept 30-Oct 1. Hope to see you there!

https://andibruce.wordpress.com/golden-oysters/